Lots of people around the world are fascinated by languages – there’s certainly a great deal of pleasure and excitement to be gained from learning and exploring a language other than your own. There are of course the practical uses of being able to understand and communicate in another language, but in addition, it opens up a whole new world to you, in terms of culture and history and plenty more.However, not everyone who learns a new language gets introduced to a new alphabet. Many languages today use the Latin script and alphabet, and it’s not just the European languages that do this. Languages across the world have switched to the Latin script from their own traditional scripts for a variety of reasons, and this certainly makes it easier for English-speaking beginners. However, for those who are fortunate enough to have the opportunity to explore a language with a different alphabet, it can be a fascinating and exciting experience.

Most people who are only familiar with their own script don’t realize that different alphabets and scripts can work in drastically different ways. The way the English or Latin alphabet works is by no means universal. In some alphabets, the basic units are not letters representing individual vowels and consonants, but “graphemes” that represent whole ideas or concepts. In others, the basic units represent syllables rather than individual sounds, and yet others are built on consonant-vowel combinations. Plenty has been said about English being crazy in the way it is written versus the way it is pronounced, but when you start to explore other alphabets, you realize that language is always a little idiosyncratic. Here are ten amazing and beautiful alphabets from around the world.

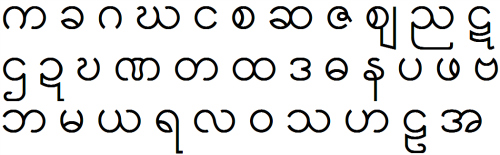

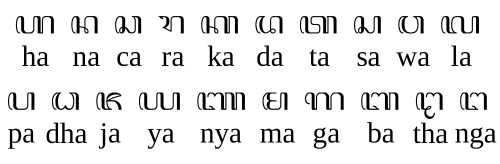

The Balinese alphabet is what is known as an abugida, a writing system where one of the main characteristics is that the basic units are consonant-vowel combinations, with the focus on the consonant. The alphabet is mainly used in Bali, Indonesia, where the alphabet is usually known as Aksara Bali or Hanacaraka. It is a descendent of the Brahmi script, and is used today to write Balinese, Old Javanese, and Sanskrit, although the first two have switched to the Latin script to a large degree.

Although the Balinese script is similar to that of many other Asian languages that share Brahmi ancestry, it is unusually elaborate and beautiful. The most common use of the alphabet today is in religious settings, such as holy manuscripts and ceremonies, especially those relating to Hinduism. In fact, it was once believed that the script itself was sacred and could not be deciphered or even taught to anyone unless they possessed the appropriate spiritual power to do so. Even today, when used in religious texts, the script uses certain “holy letters”, which are thought to have special powers beyond the sounds that they represent.

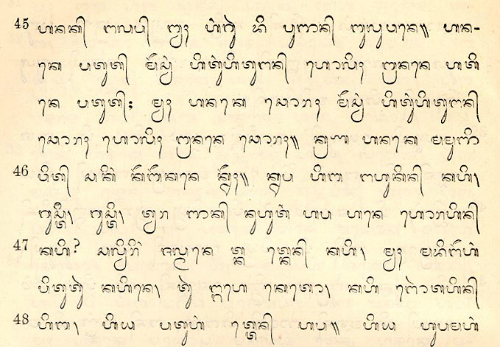

The Burmese alphabet is another descendent of the Brahmi script, and like many of its cousins, is made up of beautiful, elaborate curves and curls. The alphabet can be traced back for at least ten centuries, and like other abugidas, its letters essentially represent syllables, with markings known as “diacritics” added to the consonants in order to indicate the vowel to be used in the syllable. Traditionally, like many of the languages and alphabets it is related to, written Burmese had no spaces between words. However, contemporary use has incorporated word spacing into Burmese, since it makes text easier to read. Although the use of the Latin script to write the Burmese language is fairly common today, it is not particularly standardized, and the Burmese alphabet continues to be used quite widely. It is also used for other languages within Burma, such as Shan and Mon, as well as for religious texts that are in Sanskrit or Pali.

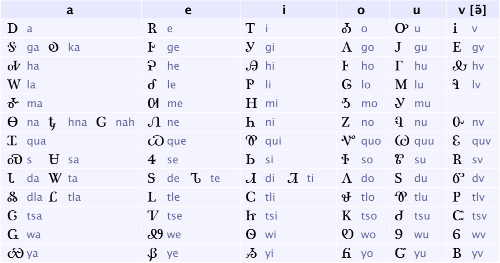

The Cherokee alphabet is one of the most exceptional alphabets in existence, largely because of how it came to be. Unlike most other scripts we know, it wasn’t developed over time, far back in history, but was invented very recently, only in the early 19th century. What’s more amazing is that it was invented by a man who, until then, could not read – not just his own Cherokee language, but any language at all. Until Sequoyah invented the Cherokee script, the Cherokee language had no writing system and its people were pre-literate. The Cherokee at the time knew of the “talking leaves” of the European settlers, but believed that writing was either fakery or sorcery. Sequoyah however believed that it was real, and felt that a script would be useful to his people.

After several unsuccessful attempts, during which he first tried to create a character for each Cherokee word and then for every possible concept, he finally created a more practical script with a character for each syllable. He based these characters on those he found in European books, but since he couldn’t read these books, the relationship between characters and sounds is his own invention, and is completely different from the original Latin or Greek letters and sounds. Sequoyah took around 12 years to complete his alphabet, but it took much less time for it to be adopted by the Cherokee people, in spite of their initial skepticism and resistance.

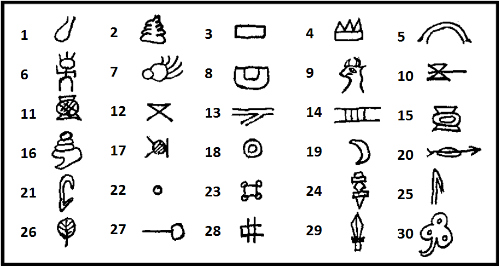

The Ersu Shaba alphabet is another rare and unique script, this time from Tibet. This is a pictographic script, and it is primarily used in religious texts and ceremonies. The words, or rather pictures, are created using a brush made of bamboo or animal hair. Apart from the style of the drawings, what makes the script unique is the fact that it uses colored inks and the colors affect the meaning. Of course, like any pictographic script, Ersu Shaba is mostly interpreted rather than read. The elements of the script represent specific concepts and objects, but they do not directly fully correspond to the Ersu language.

Even though multiple standard elements are used in a single picture, it is up to the reader to decipher the connections between the concepts and ideas, and the overall meaning. Nonetheless, the script seems to be quite elaborate and specific, because multiple readers have been found to read the same message quite consistently. The Ersu tribe itself is extremely small, and it is primarily the priests of the tribe who are able to read the script, which means that there are perhaps a maximum of ten people in the world who can read it.

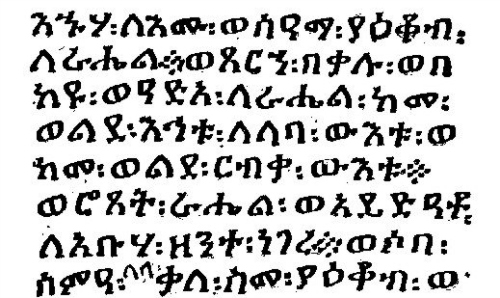

The Ge’ez alphabet is one more syllable alphabet, and the two main churches that continue to use it believe that its 26 letters were discovered through divine revelation with the intention of recording religious law. The alphabet is unusual in that the language it was first developed for (the Ge’ez language) is now no longer in use except in the religious ceremonies of a few churches, the main ones being the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church; however, the script was adopted by other languages in Ethiopia and Eritrea, which is why it is still fairly widely used. These include Semitic languages such as Amharic and Tigrinya, as well as Tigre and Blin.

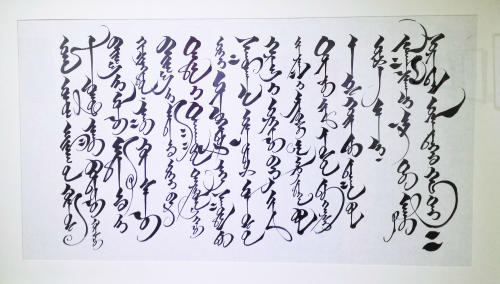

The Javanese alphabet is closely related to the Balinese alphabet, which we described earlier, and like Balinese, it too has descended from the Brahmi script. As a result, the two have many similarities – the Javanese script is also ornate and decorative, and is used by many languages in Indonesia, including Sanskrit, which is the sacred language of many religious texts and ceremonies. Both scripts are similar to many other South Asian scripts, but are said to be the most beautiful and calligraphic in their style. While the Balinese alphabet is used for Old Javanese, the Javanese alphabet is used for modern Javanese, although the use of the Latin script has grown considerably in recent times. The government has been trying to counter this by encouraging the teaching of the script in schools and its use in public signs.

The Mongolian alphabet, also known as Hudum Mongol bichig, is a beautiful vertical script that is described as a “true alphabet”, one where the letters include separate consonants and vowels. There are of course many vertical scripts in the world, but the Mongolian script is particularly beautiful and also intriguing – anyone unfamiliar with it is likely to mistake it for Arabic that is being held up the wrong way. Part of the beauty of the script is because it holds visual harmony to be very important, and the shape of a letter may be modified depending on its position and the letter that comes after it.

Another interesting fact about the Mongolian script is that even though it has the characteristics of an alphabet and can be learned letter by letter (which is how Westerners usually teach and learn it), natives tend to learn it syllable by syllable, like a syllabic language. In other words, natives don’t learn individual letters but combinations of letters that produce specific sounds in their language. Languages that use this script and adaptations of it today include Manchu, Oirat, and Xibe.

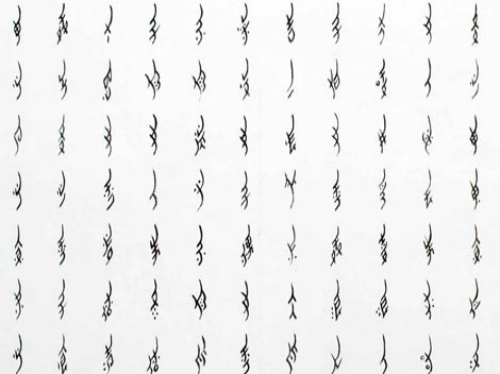

There are many beautiful and interesting scripts on this list, but probably nothing as utterly fascinating as the Nüshu script. Unfortunately, the use of Nüshu has almost entirely died out today; however, this is a script that everyone ought to know about. The name “Nüshu” literally translates to “women’s writing”, which is what it was – a script that was used exclusively by women.

Because Chinese society during the 13th and 14th centuries practiced strict segregation of the sexes and forbade women from learning to read and write, women in a remote part of the Hunan province developed this script for themselves. Nüshu was based on the Chinese script that was in use at the time, but it somewhat compressed and distorted or modified the characters so as to be unrecognizable to outsiders, and invented a few characters of its own.

The script seems to have developed over hundreds of years, and reached its peak as recently as the late 19th century. The changes that took place in the 20th century had the positive effect of allowing women access to education, but unfortunately, the downside of this was that fewer and fewer of them bothered to learn Nüshu. The line of natural transmission has now been broken, and the only people who can use Nüshu today are scholars who learned it from the last known native users.

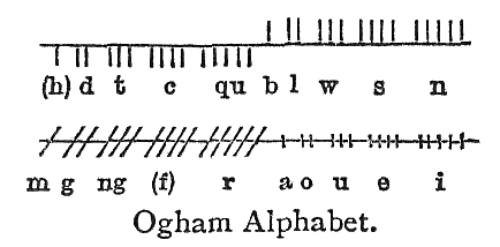

Ogham is yet another unusual and beautiful script, and most people wouldn’t even recognize it as a script. If you weren’t told, you’d probably assume it was a decorative inscription resembling a tree. You wouldn’t be entirely wrong though – the script is in fact known as the Celtic tree alphabet, and many of the letters have names that traditionally referred to trees and shrubs. Ogham was used to write early Irish and Old Irish, and although it is no longer actively used except by neo-pagans in their rituals, inscriptions can be found all over Ireland and in some parts of Britain too.

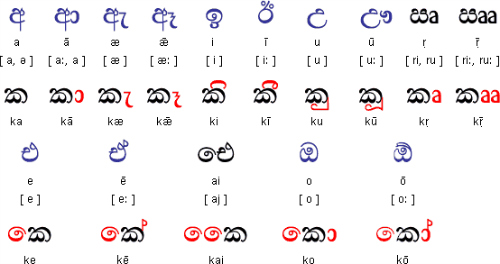

The last script on our list is another abugida, and this one is also part of the family that has descended from the Brahmi script. The Sinhala script is widely used in Sri Lanka to write the Sinhala language, as well as for Sanskrit and Pali in religious texts. The Sinhala alphabet consists of two sets of letters, which is why it is sometimes said to actually be two separate alphabets. The core set of letters is used to write words in the native Sinhala language, and an extended set is used for words from Pali, Sanskrit, and sometimes English. The Sinhala alphabet is probably the most widely used alphabet on our list. You’ll see it almost everywhere in Sri Lanka, from signboards to newspapers to books, and even as graffiti.